In a decision that may foreshadow major doctrinal change, two judges from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals have urged the court to rethink – or abandon – its long‑standing framework for assessing substantial similarity in copyright infringement cases.

Ninth Circuit Precedent: Substantial Similarity Tests

Copyright infringement cases often come down to whether the defendant’s work is “substantially similar” to the plaintiff’s copyrighted work. Under current Ninth Circuit precedent, the substantial similarity analysis follows a two-part test – the “extrinsic” test and the “intrinsic” test

- The extrinsic test is an objective inquiry that “assesses the objective similarities of the two works, focusing only on the protectable elements of the plaintiff’s expression.” The extrinsic test filters out elements that cannot be protected by copyright, such as ideas and tropes, to ensure that the works have similar specific, expressive elements.

- The intrinsic test is a subjective inquiry that asks a jury whether a reasonable observer would find substantial similarity in the “total concept and feel” of the works.

The extrinsic and intrinsic tests have been a lightning rod for criticism over time. Among other things, the tests tend to favor defendants and disfavor plaintiffs. This is because the “objective” extrinsic test can be resolved by a court at summary judgment, while the “subjective” intrinsic test is for a jury to decide. As a result, a defendant accused of infringement can sometimes win before trial, whereas a copyright plaintiff can almost never win before trial. Additionally, even when an infringement claim does go to trial, the intrinsic test’s subjectivity means that a jury verdict of no substantial similarity is effectively immune from appellate review.

Ninth Circuit Appeal: Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg

The case that may upend this two-part test is Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg, 9th Circuit Case No. 24-3367. In 1989, photographer Jeffrey Sedlik created an iconic photograph of jazz musician Miles Davis. Virtually nothing in the photograph was left to happenstance – Sedlik carefully selected the background; adjusted Davis’s hair; arranged Davis’s fingers to represent musical notes; selected Davis’s clothing; made decisions about lighting, camera positioning and camera settings; and much more. Sedlik obtained a copyright registration for the photograph and has successfully licensed it since then.

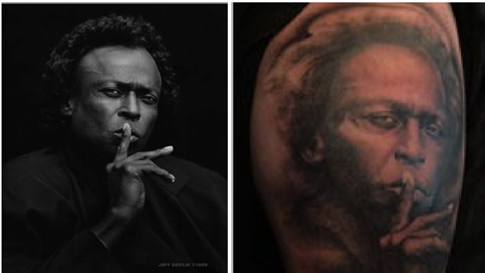

Nearly 30 years later, “Kat Von D,” a tattoo artist and celebrity, gave a friend a tattoo that was inspired by Sedlik’s photograph. She traced Sedlik’s photograph to create a tattoo stencil and had the photograph next to her as a reference during the tattoo process. Sedlik sued Kat Von D and her tattoo studio for copyright infringement because she did not have a license for the photograph. Sedlik’s photograph and the tattoo are shown below, left and right, respectively:

In 2024, a jury found in Kat Von D’s favor, finding that Sedlik did not satisfy the intrinsic test because the works did not have a substantially similar “total concept and feel.” The district court denied Sedlik’s post-trial attempts to overturn the jury’s verdict, so Sedlik appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Ruling and Calls To Abandon the Intrinsic Test

A three-judge panel begrudgingly affirmed the jury’s verdict of no infringement in an unsigned opinion, finding that under existing precedent they could not “second-guess” the jury’s verdict. The fireworks came in the concurring opinions written separately by Judges Wardlaw and Johnstone, in which both judges took the rare step of calling for the court to abandon the intrinsic test altogether. Judge Wardlaw wrote that the intrinsic test should be thrown out because it asks juries to decide complex legal questions based on their subjective impressions, not their analysis and reasoning. She noted that the intrinsic test was created by the Ninth Circuit, was “never blessed” by the United States Supreme Court, and is “virtually devoid of analysis.” She further explained that the intrinsic test undermines the entire purpose of copyright law – that is, “to protect writers from the theft of their fruits of their labor” – and “leaves the artist’s work vulnerable to clever thieves.” Judge Wardlaw would rather adopt a new test that removes the “total concept and feel” from the equation and asks juries to focus on whether there is similarity in the protectable elements of the copyrighted work.

Judge Johnstone similarly lambasted the intrinsic test as having drifted far from its original purpose and bedrock principles of copyright law. He explained that while the Ninth Circuit initially created the intrinsic test to protect “the whole of an expression,” subsequent cases have expanded the intrinsic test beyond all workability. In Judge Johnstone’s view, “What began as a factual test for determining substantial similarity of an idea’s overall expression has become a subjective test based on the jury’s own impression.” The intrinsic test has thus been “stripped away [of] any objective analysis,” rendering it “devoid of analysis.” This, Judge Johnstone warned, allows infringers to escape liability because the impressions from two works “may vary dramatically from person to person” and expert witnesses cannot offer their opinions on “total concept and feel.” Judge Johnstone also lamented the fact that plaintiffs have virtually no recourse after an unfavorable jury verdict because, as shown by this case, appellate courts cannot supplant their view of the facts for the jury’s. He joined Judge Wardlaw in calling for the Ninth Circuit to abandon the intrinsic test in favor of a more legally grounded standard focusing on protectable expression.

Implications

Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg highlights the intrinsic test’s practical shortcomings and a growing tension within the court’s substantial similarity framework. Judges Wardlaw and Johnstone’s strong concurring opinions are clear invitations for Sedlik to petition for rehearing en banc. If en banc review is granted in this case, it could signal that significant change could be on the horizon. Until then, however, litigants are stuck with the intrinsic test and must build their cases accordingly.

If you have questions about this ruling or your copyright infringement strategy, please contact Eric Sidler or Lee Bennin, or reach out to your regular Lathrop GPM attorney.